Joseph S. Renzulli, Director

The National Research Center on the Gifted and Talented

University of Connecticut

This article presents the three-ring conception of giftedness. A detailed process is presented illustrating how students can be effectively screened for gifted and talented programs through the three-ring conception approach.

Key words: screening for gifted programs, gifted, talented, identification process

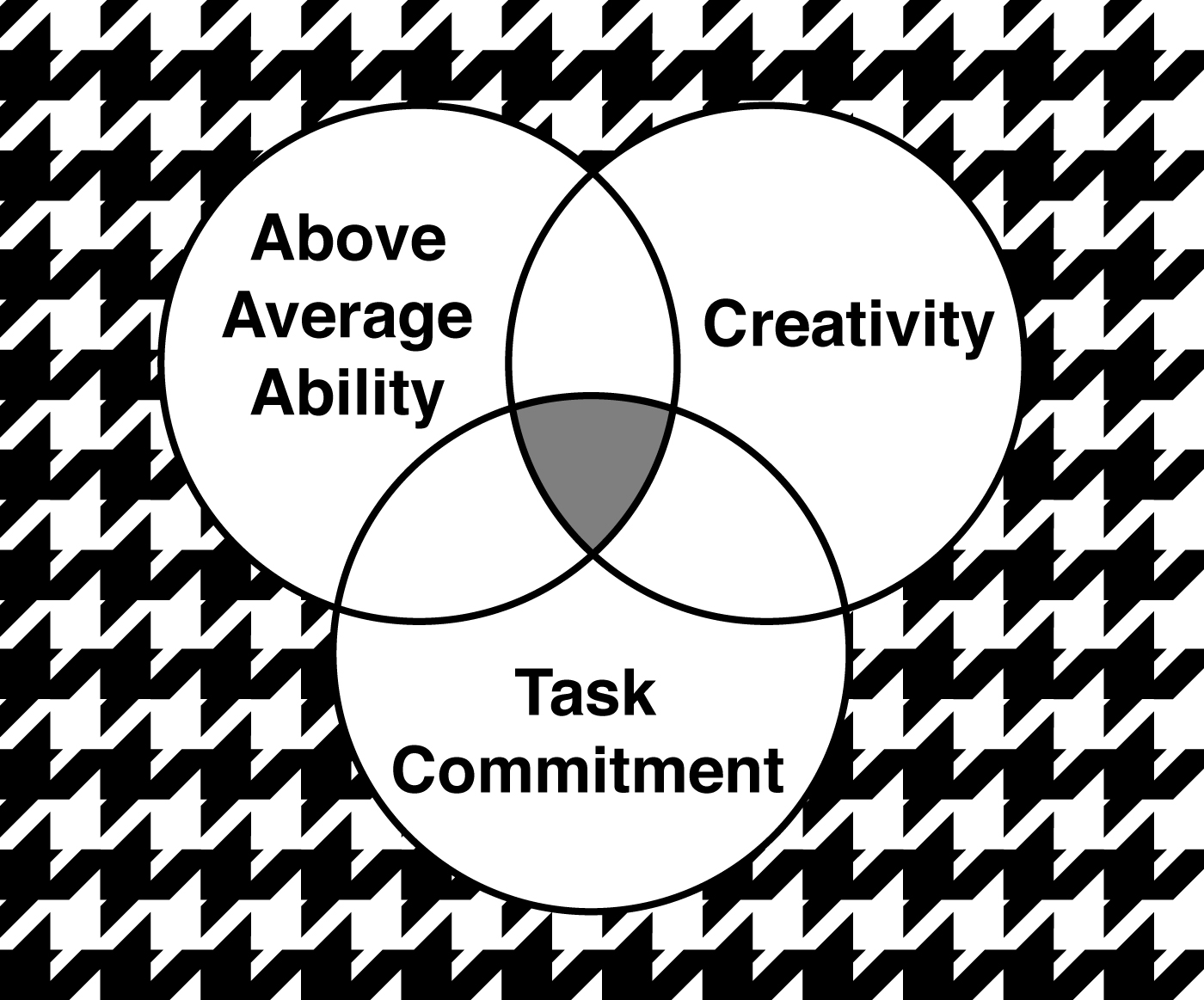

The system for identifying gifted and talented students described in this article is based on a broad range of research that has accumulated over the years on the characteristics of creative and productive individuals (Renzutli, 1986). Essentially, this research tells us that highly productive people are characterized by three interlocking clusters of ability, these clusters being above average (though not necessarily superior) ability, task commitment, and creativity. A graphic representation of this conception is presented in Figure 1. The following description of behavioral manifestations of each cluster is a summary of the major concepts and conclusions emanating from the work of theorists and researchers who have examined these concepts:

Well Above Average Ability

Adaptation to the shaping of novel situations encountered in the external environment.

The automatization of information processing; rapid accurate, and selective retrieval of information.

Specific Ability

The capacity for acquiring and making appropriate use of advanced amounts of formal knowledge, tacit knowledge, technique, logistics, and strategy in the pursuit of’ particular problems or the manifestation of specialized areas of performance.

The capacity to sort out relevant and irrelevant information associated with a particular problem or areas of study or performance.

Task Commitment

The capacity for perseverance. endurance. determination, hard work, and dedicated practice. Self-confidence. a strong ego and a belief in one’s ability to carry out important work, freedom from inferiority feelings, drive to achieve.

The ability to identify significant problems within specialized reason; the ability to tune in to major channels of communication and new developments within given fields. Setting high standards for one’s work; maintaining an openness to self and external criticism; developing an aesthetic sense of taste, quality, and excellence about one’s own work and the work of others.

Creativity

Openness to experience; receptive to that which is new and different (even irrational) in thoughts, actions, and products of oneself and others.

Curious, speculative, adventurous, and “mentally playful” willing to take risks in thought and action, even to the point of being uninhibited.

Sensitive to detail, aesthetic characteristics of ideas and things; willing to act on and react to external stimulation and one’s own ideas and feelings.

Figure 1. What makes giftedness?

As is always the case with lists of traits such as the above, there is an overlap among individual items, and an interaction between and among the general categories and the specific traits. It is important to point out that all the traits need not be present in any given individual or situation to produce a display of gifted behaviors. It is for this reason that the three ring conception of giftedness emphasizes the interaction among the clusters rather than any single cluster. It should also be emphasized that the above average ability cluster is a constant in the identification system described below. In other words, the well above average ability group represents the target population and the starting point for the identification process. and it will be students in this category that are selected through the use of test score and non-test criteria. Task commitment and creativity, on the other hand, are viewed as developmental goals of the special program. By providing above average ability students with appropriate experiences, the programming model (Renzulli. 1977) for which this identification system was designed serves the purpose of promoting creativity and task commitment, and in “bringing the rings together” to promote the development of gifted behaviors.

In the sections that follow, I will outline the specific steps of an identification system that is designed to translate the three-ring conception of giftedness into a practical set of procedures for selecting students for special programs. The focal point of this identification system is a Talent Pool of students that will serve as the major (but not the only) target group for participation in a wide variety of supplementary services. The goals of this identification system, as it relates to the three-ring conception of giftedness are threefold:

- To develop creativity and/or task commitment in Talent Pool students and other students who may come to our attention through alternate means of identification.

- To provide learning experiences and support systems that promote the interaction of creativity, task commitment, and above average ability (i.e., bring the “rings” together)

- To provide opportunities, resources, and encouragement for the development and application of gifted behaviors.

Before listing the steps involved in this identification system, three important considerations will be discussed. First, Talent Pools will vary in any given school depending upon the general nature of the total student body. In school with unusually large numbers of high ability students, it is conceivable that Talent Pools will extend beyond the 15 percent level that is ordinarily recommended in schools that reflect the achievement profiles of the general population. Even in schools where achievement levels are below national norms, there still exists an upper level group of students who need services above and beyond those which are provided for the majority of the school population. Some of our most successful programs have been in inner-city schools that serve disadvantaged and bilingual youth; and even though these schools were below national norms, a Talent Pool of approximately 15 percent of higher ability students needing supplementary services was still identified. Talent Pool size is also a function of the availability of resources (both human and material). and the extent to which the general faculty is willing (a) to make modifications in the regular curriculum for above average ability students, (b) to participate in various kinds of enrichment and mentoring activities, and (c) to work cooperatively with any and all personnel who may have special program assignments.

Since teacher nomination plays an important role in this identification system, a second consideration is the extent of orientation and training that teachers have had about both the program and procedures for nominating students. In this regard, we recommend the use of a training activity that is designed to orient teachers to the behavioral characteristics of superior students (Renzulli & Reis, pp. 203-2 10).

A third consideration is, of course. the type of program for which students are being identified. The identification system that follows is based on models that combine both enrichment and acceleration, whether or not they are carried out in self-contained or pull-out programs. Regardless of the type of organizational model used, it is also recommended that a strong component of curriculum compacting (Renzulli, Smith, & Reis, 1982) be a part of the services offered Talent Pool students.

For purpose of demonstration, the example that follows will be based oil the formation of a 15 percent Talent Pool. Larger or smaller Talent Pools can be formed by simply adjusting the figures used in this example.

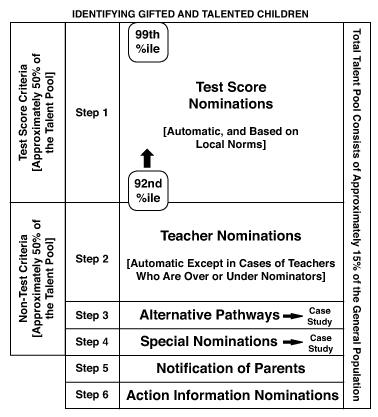

Step 1: Test Score Nominations

If we were using nothing but test scores to identify a 15 percent Talent Pool, the task would be ever so simple! Any child who scores above the 85th percentile (using local norms) would be a candidate. In this identification system, however, we have made a commitment to “leave some room” in the Talent Pool for students whose potentials may not be reflected in standardized tests. Therefore, we will begin by dividing our Talent Pool in half (see Figure 2), and we will place all students who score at or above the 92nd percentile (again, using local norms) in the Talent Pool. This approach guarantees that all traditionally bright youngsters will automatically be selected, and they will account for approximately 50 percent of our Talent Pool. This process guarantees admission to bright underachievers.

Figure 2. The Renzulli identification system

Any regularly administered standardized test (e.g., intelligence, achievement, aptitude) can be used for this purpose, however, we recommend that admission to the Talent Pool be granted on the basis of any single test or subtest score. This approach will enable students who are high in verbal or non-verbal ability (but not necessarily both) to gain admission, as well as students who may excel in one aptitude (e.g., spatial, mechanical). Programs that focus on special areas such as the arts, leadership, and athletics should use non-test criteria as major indicators of above ability in a particular talent area. In a similar fashion, whenever test scores are not available, or we have some question as to their validity, the non-test criteria recommended in the following steps should be used. This approach (i.e., the elimination or minimization of Step 1) is especially important when considering primary age students, disadvantaged populations, or culturally different groups.

Step 2: Teacher Nominations

The teacher should be informed about all students who have gained entrance through test score nominations so that they will not have to engage in needless paperwork for students who have already been admitted. Step 2 allows teachers to nominate students who display characteristics that are not easily determined by tests (e.g., high levels of creativity, task commitment, unusual interest, talents. or special areas of superior performance of potential). With the exception of teachers who are over nominators or under nominators, nominations from teachers who have received training in this process are accepted into the Talent Pool on an equal value with test score nominations. That is, we do not refer to students nominated by test scores as the “truly gifted,” and the students nominated by teachers as the moderately or potentially gifted. Nor do we make any distinctions in the opportunities, resources, or services provided, other than the normal individualization that should be a part of any program that attempts to meet unique needs and potentials. Thus, for example, if a student gains entrance on the basis of teacher nomination because he or she has shown advanced potential for creative writing, we would not expect this student to compete on an equal basis in mathematics With a student who scored at or above the 92nd percentile on a math test. Nor should we arrange program experiences that Would place the student with talents in creative writing in an advanced math cluster group. Special programs should first and foremost respect and reflect the individual characteristics that brought students to our attention in the first place.

A teacher nomination form and rating scales (Renzulli, et al., 1976) are used for this procedure. The rating scales are not used to eliminate students with lower ratings. Instead, the scales are used to provide a composite profile of the nominated students. In cases of teachers who are over nominators, a request is made that they rank order their nominations for review by a schoolwide committee. Procedures for dealing with under-nominators or non-nominators will be described in Step 4.

Step 3: Alternate Pathways

Whereas all schools using this identification system make use of test score and teacher nominations, alternate pathways are considered to be local options, and are pursued in varying degrees by individual school districts. Decisions about which alternative pathways might be used should be made by a local planning committee, and some consideration should be given to variations in grade level. For example, self-nomination is more appropriate for students who may be considering advanced classes at the secondary level.

Alternate pathways generally consist of parent nominations, peer nominations, tests of creativity, self-nominations, product evaluations and virtually any other procedure that might lead to initial consideration by a screening committee. The major difference between alternate pathways on one hand, and test score and teacher nomination on the other, is that alternate pathways are not automatic. In other words, students nominated through one or more alternate pathways will be reviewed by a screening committee, after which a selection decision will be made. In most cases the screening committee carries out a case study that includes examination of all previous school records, interviews with students, teachers, and parents, and the administration of individual assessments that may be recommended by the committee. In some cases, students that are recommended on the basis of one or more alternate pathways are placed in the program on a trial basis.

Step 4: Special Nominations (Safety Valve No. 1)

Special nominations represent the first of two “safety valves” in this identification system. This procedure involves circulating a list of all students who have been nominated through one of the procedures in Steps 1 through 3 to all teachers within the school, and in previous schools if students have matriculated from another building. This procedure allows previous year teachers to nominate students who have not been recommended by their present teacher, and it also allows resource teachers to make recommendations based on their own previous experience with students who have already been in the Talent Pool, or students they may have encountered as part of enrichment experiences that might have been offered in regular classrooms. This step allows for a final review of the total school population, and is designed to circumvent the opinions of present year teachers who may not have an appreciation for the abilities, style, or even the personality of a particular student. One last “sweep” through the population also helps to pick up students that may have “turned-off” to school or developed patterns of underachievement as a result of personal or family problems. This step also helps to overcome the general biases of an under nominator or a non-nominator. As with the case of alternate pathways, special nominations are not automatic. Rather, a case study is carried out and the final decision rests with the screening committee.

Step 5: Notification and Orientation of Parents

A letter of notification and a comprehensive description of the program is forwarded to the parents of all Talent Pool students indicating that their youngster has been placed in the Talent Pool for the year. The letter does not indicate that a child has been certified as “gifted,” but rather explains the nature of the program and extends an invitation to parents for an orientation meeting. At this meeting a description of the three-ring conception of giftedness is provided, as well as an explanation of all program policies, procedures, and activities. Parents are informed about how admission to the Talent Pool is determined, that it is carried out on an annual basis, and that additions to Talent Pool membership might take place during the year as a result of evaluations of student participation and progress. Parents are also invited to make individual appointments whenever they feel that additional information about the program in general, or their own child, is required. A similar orientation session is provided for students, with emphasis once again being placed on the services and activities being provided. Students are not told that they are “the gifted,” but through a discussion of the three-ring conception and the procedures for developing general and specific potentials, they come to understand that the development of gifted behaviors is a program goal as well as part of their own responsibility.

Step 6: Action Information Nominations (Safety Valve No. 2)

In spite of our best efforts, this system will occasionally overlook students, who, for one reason or another, are not selected for Talent Pool membership. To help overcome this problem, orientation related to spotting unusually favorable “turn-ons” in the regular curriculum is provided for all teachers. In programs following the Schoolwide Enrichment Model (Renzulli & Reis, 1983), we also provide a wide variety of in-class enrichment experiences that might result in recommendations for special services. This process is facilitated through the use of a teacher training activity and an instrument called an Action Information Message (Renzulli & Reis, 1985, pp. 41-42, 398-403).

Action information can best be defined as the dynamic interactions that occur when a student becomes extremely interested in or excited about a particular topic, area of study, issue, idea or event that takes place in school or the nonschool environment. It is derived from the concept of performance based assessment, and it serves as the second safety valve in this identification system. The transmission of an action information message does not mean that a student will automatically revolve into advanced level services, however, it serves as the basis for a careful review of the situation to determine if such services are warranted. Action information messages are also used within Talent Pool settings (i.e., pull-out groups, advanced classes, cluster groups) to make determinations about the pursuit of individual or small group investigations (Type III Enrichment in the Triad Model).

DISCUSSION

In most identification systems that follow the traditional screening-plus-selection approach, the “throw aways” have invariably been those students who qualified for screening on the basis of nontest criteria. Thus, for example, a teacher nomination is only used as a ticket to take an individual or group ability test, but in most cases the test score is always the deciding factor. The many and various “good things” that led to nominations by teachers are totally ignored when it comes to the final (selection) decision, and the multiple criteria game ends up being a smoke screen for the same old test based approach.

The implementation of the identification system described above has helped to overcome this problem as well as a wide array of other problems traditionally associated with selecting students for special programs. Generally, students, parents, teachers, and administrators have expressed high degrees of satisfaction with this approach (Renzulli, 1988), and the reason for this satisfaction is plainly evident. By “picking up” that layer of students below the top few percentile levels usually selected for special programs, and by leaving some room in the program for students to gain entrance on the basis of nontest criteria, we have eliminated the justifiable criticisms of those persons who know that these students are in need of special opportunities, resources, and encouragement. The research underlying the three-ring conception of giftedness clearly tells us that such an approach is justified in terms of what we know about human potential. And by eliminating the endless number of “headaches” traditionally associated with identification, we have gained an unprecedented amount of support from teachers and administrators, many of whom, formerly resented the very existence of special programs.

The Achilles Heel of Change

Even modest changes in the status quo inevitably raise concerns and questions on the parts of practitioners who might be affected by the proposed changes. One of the most frequently asked questions about the changes in identification procedures described above is: “How will this approach ‘square’ with state guidelines?” Before answering this question, I would like to point out that I have not expressed dissatisfaction with the restrictiveness of identification guidelines. The research cited above, and the contributions of leaders in the field such as Bloom (1985), Gardner (1983), Guilford (1977), Sternberg (1983). Treffinger (1982), and Torrance (1979) clearly point the need for a reexamination of the regulations under which most programs are forced to operate. This research is so supportive of a more flexible approach to identification that the rationale for change no longer needs to be argued. Guidelines should be our servants, not our masters. but if we are to gain more control over our own destiny, we must take concrete steps to bring existing guidelines into title with present day theory and research.

Fortunately, change is in the wind, and a bold new breed of leadership in gifted education is emerging in many state departments of education. These persons have been willing to reexamine present guidelines, and even in the absence of immediate changes, they have allowed for much more flexibility in the interpretation of existing regulations. Proposals that only a few years ago were being rejected because they did not meet strict cut-off score requirements. are now being accepted and even encouraged.

The Achilles Heel of change is not guidelines, but apathy. If we believe that more flexibility is desirable, we must mobilize professional personnel who have a stake in serving high potential youth. Principals, teachers, superintendents and pupil personnel specialists should be recruited for organized statewide efforts directed toward guidelines that are more responsive to contemporary research. Carefully selected research based documents should be brought to the attention of state boards of education and the education committee of the legislatures. Every effort should be made to develop reimbursement formulas that are based on total district enrollment rather than the number of students identified. It has been this “body count” approach that has forced schools to treat giftedness as an absolute State of being rather than a developmental concept, and the result has been the most rigid kinds of test score identification procedures. By getting rid of the body count approach to identification, we will allow districts greater flexibility in the types of identification and programming models they might want to consider (including test-based approaches), and we will provide greater equity for districts that serve disadvantaged and culturally diverse populations.

To be certain, there will be a little less tidiness in the identification process, but the trade off for tidiness and administrative expediency will result in many more flexible approaches to both identifying and serving young people with great potential. From a research perspective, new data will be yielded, and thus, new dialogue and controversy will emerge. This is indeed how science goes on forever, how new ideas and insights are realized, and how a field of study continues to improve and to revitalize itself.

References