Commentary [10-6-20]

Joseph S. Renzulli

Laurel E. Brandon

University of Connecticut

This brief Commentary is intended to call attention to the important difference between Assessment For Learning and Assessment Of Learning. Classic measurement theory makes a distinction between these two types of assessment. Assessment of learning, called summative assessment, is used to evaluate student content learning, skill acquisition, and academic achievement at the conclusion of a defined instructional period—typically at the end of a project, unit, course, semester, program, or school year. Summative assessments are generally formal, structured, norm or criterion referenced, and often used to normalize performance so that students can be measured, compared, and then remediated, usually through skill targeted drill and practice instruction. This type of assessment has dominated most school related decision making through the use of state administered standardized achievement tests.

Assessment for learning falls into the category called formative assessment. Formative assessment is ongoing, flexible, and usually informal, and it includes information that is gathered for the purposes of modifying instruction during an individual lesson or for future instructional planning. It is based on information gathered from the students during or prior to instruction (i.e., pre-assessment); and is used to adapt teaching to meet student needs. Both types of assessment are important but, “Formative assessment with appropriate feedback is the most powerful moderator in the enhancement of achievement” (Hattie et al., 2007). Assessment for learning gathers data, usually from the students themselves, and focuses on students as individuals. These data typically include interests, instructional style preferences, preferred modes of expression, and other co-cognitive factors. This type of information provides insights into how teachers can modify teaching and learning activities for individuals.

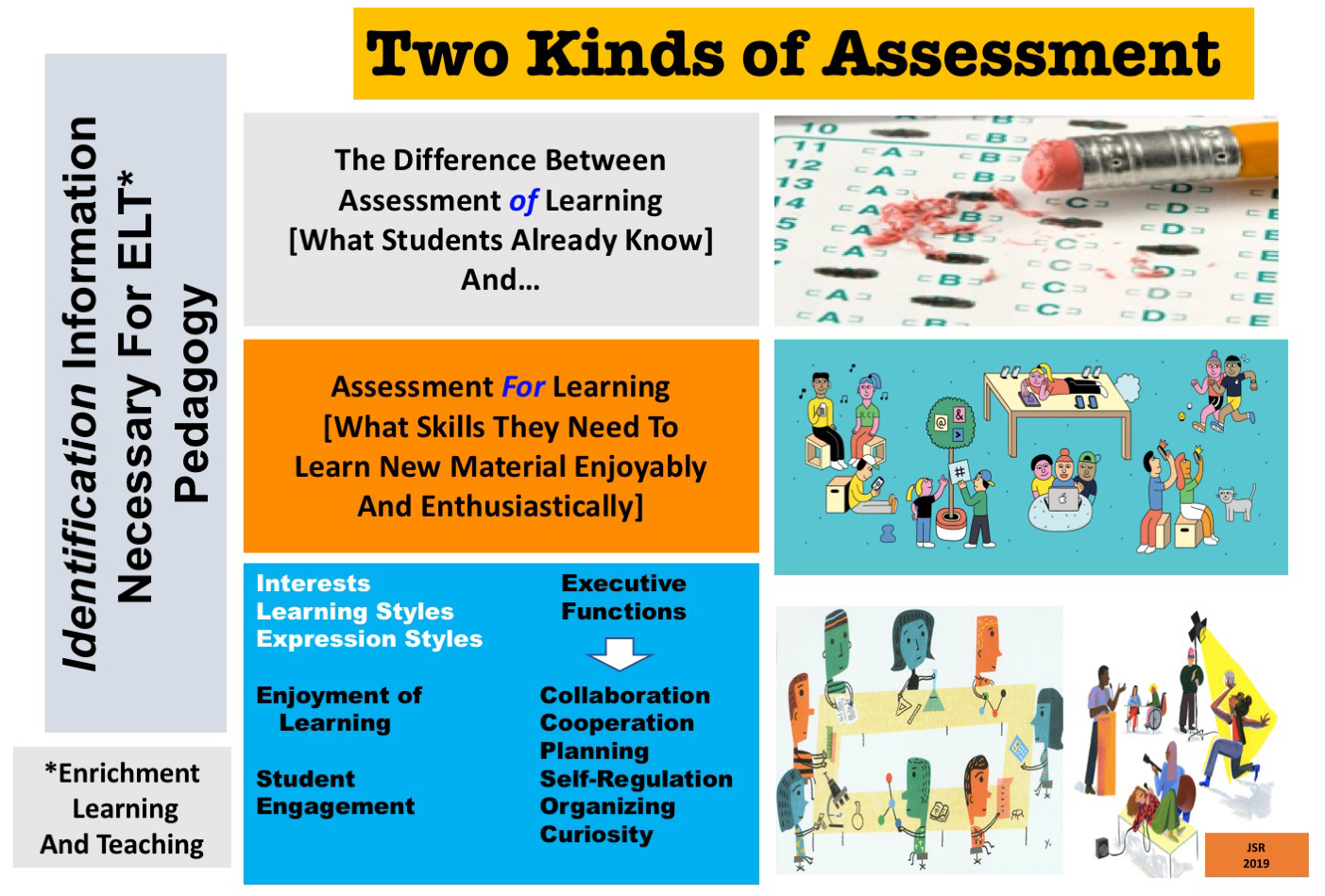

The focus of the remainder of this commentary will be the type of assessment for learning that emphasizes students’ individual learning characteristics and preferences. This type of assessment focuses on individual rather than group data and is not used to rank students, though it can be used to form small groups who share relevant interests or other characteristics. A figural representation of these two types of assessment and suggested characteristics that should be a focus of assessment for learning is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1

Two Types of Assessment

One of the fastest growing topics in the identification of young people for talent development opportunities is a focus on non-cognitive skills variously referred to as “soft skills,” “character skills,” “social intelligence,” and “executive function skills.” One of the reasons for this new emphasis is the greater attention being paid to these skills by both college admissions officers and human resource specialists in all areas of job employment, especially for high level jobs that require leadership, innovation, and the ability to work collaboratively with others. Although these skills are not as easily measured as the cognitive skills measured by standardized aptitude and achievement tests, they are, nevertheless, adding a new dimension to the ways in which we look at human potential. They also cannot be taught or evaluated in the same didactic and prescriptive manner that we teach young people to memorize information for traditional “right-answer” tests. And since today’s emphasis on social emotional development is consistent with the types of skills described below, this work gives some direction to the social and emotional skills whose importance has recently been recognized and that are now being included in educational planning.

Developing Students’ Executive Function Skills

These skills are challenging to place into a workable framework, and there is a great deal of interaction between and among the many skills that have been identified as important in the taxonomy shown in Figure 2. Indeed, several of these skills could potentially be categorized under other headings, and one of the goals of our current research is to determine the most accurate organizational structure for understanding these skills. We feel there is sufficient evidence in the soft skill literature to support some general suggestions about the types of pedagogy that are likely to make developing these skills enjoyable and engaging for both teachers and students (Anderson, 2002; Culclasure et al., 2019; Dawson & Guare, 2004; National Research Council et al., 2012; Ornellas et al., 2019).

The best way to develop these skills in young people is to provide them with experiences in which executive function skills must be used rather than taught through direct instruction. Simulations and project-based learning are authentic ways of getting students both academically and socially and emotionally involved in more real-world experiences. Simulations are instructional scenarios where the learner is placed in a situation defined by the teacher. They represent a reality within which students interact. The teacher controls the parameters of the situation and serves as the guide-on-the-side rather than the information giver. Asking students, for example, to play different roles in designing a safe playground for preschool children, planning a school magazine or school ground exercise program, or dealing with a bullying situation are all easy ways to promote the cognitive as well as non-cognitive traits that are part of learning new skills. Thousands of free game-based simulations can be found on-line (e.g., https://www.learn4good.com/kids-games/simulation.htm) that simulate everything from learning to fly an airplane to building a zoo or dissecting and preserving your own mummy. Publications on Interact sites such as Social Studies School Service offer simulation-based curricular units for social studies, math, science, and literacy (https://www.socialstudies.com/?s=Interact&fwp_search_facet=Interact).

Real-world projects from examples we have seen such as putting on a school book sale or building hydroponic gardening tables for senior centers are excellent ways for students to develop empathy and the cooperative and collaborative skills that are mentioned in the taxonomy. These projects also provide a real-world application of curricular topics (e.g., math skills in a school store; biological knowledge for a hydroponic garden).

A key to successful project-based learning is to give students a choice in the area in which they would like to work. In teacher-initiated projects, students may wish to choose their role within the overall project (such as designing the hydroponic setup or selecting appropriate plants in the gardening tables for senior centers example mentioned above). In our enrichment cluster program1 (Renzulli et al., 2013), students choose both the topic and the various role(s) they would like to play in the project. First, they select the cluster of greatest interest in which to participate, and then they select what role they will play to support the cluster’s major goal, which is to produce a product, performance, or presentation that is designed to have an impact on one or more targeted audiences. We have observed many of the executive functions “coming together” as students in enrichment clusters have worked cooperatively to bring their audience- oriented projects to the highest possible level of development. We sometimes describe this type of work as encouraging young people to be thinking, feeling, and doing like practicing professionals, even if their work is at a more junior level than adult professionals in a given field.

Executive functions contribute to improved academic outcomes as well as supporting social and emotional learning, self-confidence, and self-efficacy (Culclasure et al., 2019; Durlak et al., 2011; Richardson et al., 2010). By prioritizing the integration of academic and executive functions skills, we can make learning a more enjoyable and engaging process. The key to successfully integrating cognitive and co-cognitive skills is to avoid the direct teaching of executive function skills, focus on the project-based learning method, providing teacher guidance on locating and using how-to information, and emphasize the importance on student-selected product genre, design, format, and target audiences.

Summary

Assessment For Learning is a personalized approach to providing young people with opportunities, resources, and encouragement to develop their special interests and talents and encouraging them to express themselves in preferred modes of communication. We don’t want to fall into the norms trap that overshadows summative assessment and even the use of local norms, both of which are widely used to create percentiles and other statistics for making comparisons between and among students of various age and demographic groups. A personalized approach simply means that students examine themselves by responding to surveys about themselves, and that teachers use this information to make informed decisions about how to capitalize on student interests and strengths. We have already developed a number of these instruments (Interests, Learning Styles, and Expression Styles) and have included them in the Student Profiler that is part of the Renzulli Learning System (https://renzullilearning.com/).

We are currently seeking teachers to help us validate an instrument for assessing students’ executive functions (http://s.uconn.edu/efpilot2), and we plan to develop a student-completed version in the near future. We are also creating two other tools that teachers and their students will complete to examine the students’ perceptions of learning at school. One tool is designed to measure perceptions of School Relationships, Enjoyment of Learning, and Engagement in Learning, and the other is designed to provide a profile of the types of enriched educational experiences students perceive. We hope that these measures can later be used to examine correlations between these perceptions and more traditional objective measures, such as academic outcomes and attendance. Please contact Laurel Brandon if you would like to participate in the development of these two tools. We will need approximately 200 teachers and their classes to participate for the statistical validation of the tools.

A major challenge facing the field of education of the gifted and talented is the underrepresentation of low income and minority students as well as students who have been labeled twice exceptional (extremely high ability while simultaneously being challenged with learning disabilities). In order to open the door wider for these students to have access to talent develop opportunities we must not ignore traditional normative approaches; however, we must be flexible enough to add the important information that can be gained through assessment for learning.

Figure 2

Taxonomy of Executive Function Skills

Goal setting

Decision Making Networking Organization

Perseverance & Persistence

Time Management

Delegation of Responsibilities

Focus

Attention to Details

Innovation and Creativity

Appraisal of Personal Strengths and Weaknesses

Confidence in Leadership Skills

Willingness to Accept and Act Upon

Constructive Feedback

Optimism

Self-Management

Self-Motivation

Sense of Humor

Listening

Written, Verbal, and Non-Verbal communication

Friendliness

Respect for the Opinions of Others

Cooperation and Collaboration

Tolerance

Generosity

Kindness

Patience

Calmness

Trust

Teamwork

Positive Reinforcement

Recognition of Other’s Strengths

Negotiation and Mediation

Openness to Idea Exchange

1 For persons not familiar with our enrichment cluster program, a brief article summarizing the book on this topic can be found at https://gifted.uconn.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/961/2022/06/Enrichment_Clusters.pdf

References