Del Siegle

D. Betsy McCoach

Anne Roberts

Note: This document is not the copy of record and may not exactly replicate the authoritative document published in High Ability Studies. When referencing this work please refer to and cite the published article: Siegle, D., McCoach, D. B., & Roberts, A. (2017). Why I believe I achieve determines whether I achieve. High Ability Studies, 28(1), 59-72. https://doi.org/10.1080/13598139.2017.1302873

Why do some high-ability students embrace their ability and achieve while other equally talented students fail to academically engage? One possible reason is the beliefs and values (see McCoach, Gable, & Madura, 2013 for a discussion of values, beliefs, and attitudes) students hold toward themselves, given tasks, and achievement itself. Beliefs and values help to shape and regulate behaviors. Beliefs about students’ own abilities, as well as whether they value school and teachers can influence students’ achievement (McCoach & Siegle, 2003a).

Previous research on underachievement and motivation theory provides a clue to what beliefs and values may be important for achievement. On the basis of this previous research, we developed the Achievement Orientation Model (AOM; Siegle & McCoach, 2005). This model is based upon Bandura’s self-efficacy theory (Bandura, 1986), Weiner’s attribution theory (Weiner, 1986), Eccles’ expectancy-value theory (Eccles & Wigfield, 1995), person-environment fit theory (French, Rodgers, & Cobb, 1974; Lewin, 1935) and Rotter’s (1966) locus of control theory.

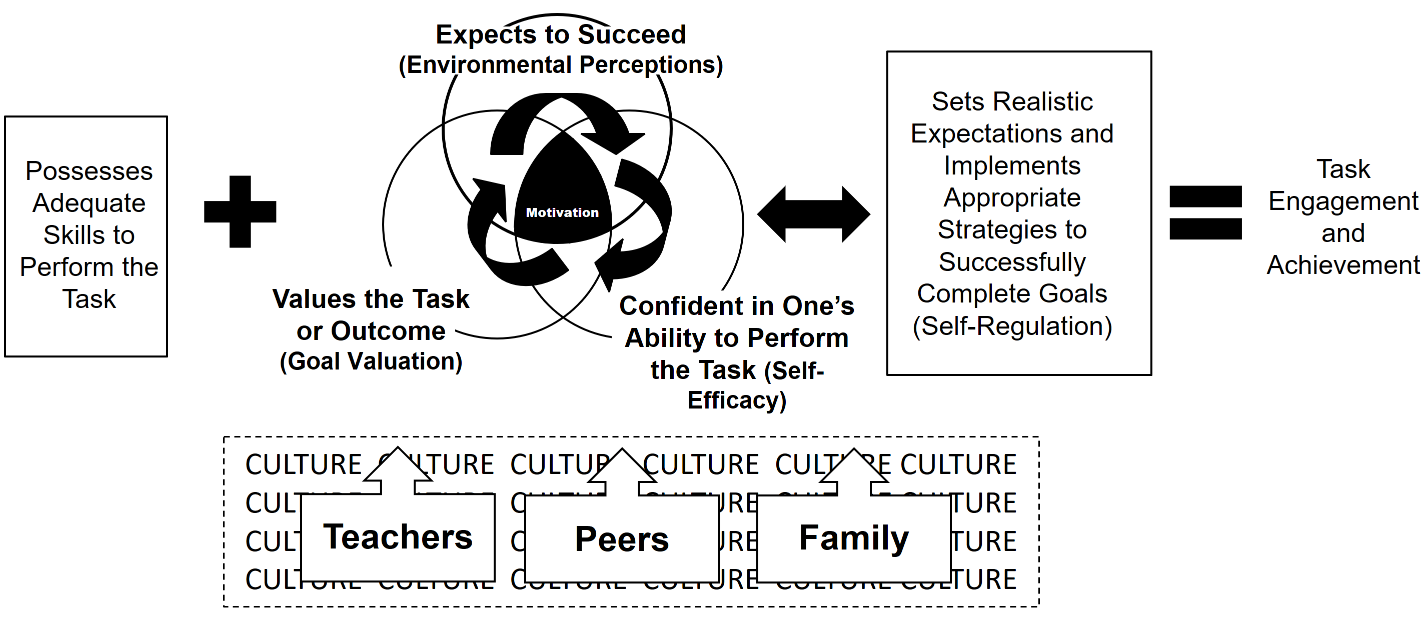

This paper presents a refinement of the Achievement Orientation Model by clarifying the relationships among the four key components. As before, individuals’ self-perceptions in three areas, self-efficacy, goal valuation, and environmental perceptions, regulate students’ motivation, and subsequently interact with self-regulation to promote engagement and ultimately achievement. Accordingly, individuals must possess positive affect in the areas of self-efficacy, goal valuation, and environmental perceptions. The intensity of their positivity in the three areas need not be equally strong, but it must be positive. We have been less clear in previous publications (Siegle & McCoach, 2005) about the multiplicative and additive nature of the components. The three attitudes operate in a multiplicative manner similar to Simonton’s (2005) Emergenic-Epigenetic model. If any of the three do not meet a “threshold” value, students may fail to be motivated. Intense positivity in one of the three areas does not compensate for negativity in one of the other areas. However, beliefs and values are not enough: It is the addition of the self-regulation metacognitive process that ultimately results in achievement (Brigandi, 2015). Therefore, the model is a combination of multiplicative and additive features. If any one of the three attitude components is missing, regardless of the strength of the others, individuals lack the motivation to self-regulate and achievement may falter. Although lacking the product of the three attitudes hinders motivation, possessing them does not guarantee achievement, because self-regulation is still necessary. Societal and cultural values also influence students’ beliefs and values in the three areas of self-efficacy, goal valuation, and environmental perceptions, as well as their self-regulation, through students’ interactions with peers, parents, and teachers. The bottom section of Figure 1 depicts this process.

Figure 1. The Achievement Orientation Model (reprinted with permission of Del Siegle)

In addition to our own research on the model (Brigandi, Siegle, Weiner, Gubbins, & Little, 2016; McCoach, 2002; McCoach & Siegle, 2001, 2003a; Rubenstein, Siegle, Reis, McCoach, & Burton, 2012; Siegle, McCoach, & Shea, 2014; Siegle, Rubenstein, & Mitchell, 2014), other researchers have found that the elements in the model, as measured by the School Attitude Assessment Survey-Revised (SAAS-R; McCoach & Siegle, 2003b) predict educational aspirations (Kirk et al., 2012) and are able to differentiate high and low achievers at different ages and in a variety of countries (Davie, 2012; Figg, Rogers, McCormick, & Low, 2012; Long & Erwin, 2016; Perez, Costa, Corbi, & Iniesta, 2016; Ritchotte, Matthews, & Flowers, 2014; Suldo, Shaffer, & Shaunessy, 2008).

Background

A multitude of factors can influence academic achievement, including students’ perceptions of themselves, as well as students’ perceptions of their environment and the support it does or does not provide. Within these categories, students’ attitudes toward curriculum (VanTassel-Baska & Little, 2017), goal orientation, mindset (Dweck, 2006), self-efficacy (Bandura, 1986), and self-regulation (Zimmerman, 2011) are all crucial motivational processes that influence the achievement process. Need for cognition (NFC) may also influence student achievement (Meier, Vogl, & Preckel, 2014; Preckel, Holling, & Vock, 2006). Students’ values and beliefs in these various constructs ultimately determine whether they achieve, to what extent they achieve, and in which settings they achieve. The Achievement Orientation Model suggests that students’ self-efficacy beliefs, as well the tasks they value and their beliefs about the environmental support they receive ultimately determine their willingness to self-regulate and achieve.

Self-Efficacy

Bandura introduced the concept of self-efficacy in 1977, when he defined it as “the conviction that one can successfully execute the behavior required to produce the outcome” (p. 79). Decades of research support the positive relationship between believing one has the capacity to perform an academic task and actual academic achievement (Artino, 2012; Multon, Brown, & Lent, 1991; Robbins, Lauver, Le, Davis, Langley, & Carlstrom, 2004). Individuals with low self-efficacy toward a task are more likely to avoid it, while those with high self-efficacy are more likely to attempt it. These individuals will work harder at the task and will persist longer in the face of difficulties (Ames & Archer, 1988; Bandura, 1977, 1986; Schunk, 1981; Schunk & Pajares, 2013). In an educational setting, self-efficacy influences: (1) the activities students select, (2) how much effort they put forth, (3) how persistent they are in the face of difficulties, and (4) the difficulty of the goals they set. Students with low self-efficacy do not expect to do well. They do not believe they have the skills to do well and may avoid tasks for which they are not efficacious. Gifted students with low self-efficacy often do not achieve at a level that is commensurate with their abilities. The connection between self-efficacy and achievement grows stronger as students advance through school and is highly predictive of achievement at the college level (Wood & Locke, 1987).

Over the last decade, educators and researchers have become concerned not only about whether students are efficacious about their abilities, but how they believe they obtained their abilities and the skills they need to be successful. Dweck’s (2006, 2012) work on growth mindsets propelled this issue to the forefront for practitioners and researchers. Dweck (2012) stressed the importance of students seeing talents and abilities as dynamic and malleable qualities. Students who see their abilities as something they can develop, rather than simply a fixed trait, are more motivated to learn and persevere more in the face of obstacles, are more resilient after setbacks, and ultimately achieve more. It is this growth mindset that leads to positive achievement behaviors (Dweck, 2006).

Dweck (2012) cautioned educators to carefully consider how they portray giftedness to students and how they encourage students who excel. This is particularly important for students who are identified for gifted and talented programs. Past research (Heller & Ziegler, 1996, 2001; McNabb, 2003; Siegle & Reis, 1998) suggested that students who are identified as gifted tend to attribute their achievement more to ability than effort. Such beliefs are often associated with a fixed, rather than a growth mindset. Students with a fixed mindset believe abilities are innate and cannot be changed. Educators of the gifted face a dilemma of how to recognize outstanding student achievement, and the accompanying ability, if they wish to promote a growth mindset (Makel, Snyder, Thomas, Malone, & Putallaz, 2015; Siegle, 2012; Siegle & Langley, 2016; Siegle et al., 2010; Snyder, Barger, Wormington, Schwartz-Bloom, Linnenbrink-Garcia, 2013). The dilemma is recognizing high abilities, promoting self-efficacy, and encouraging a growth mindset. A talent development approach to giftedness (Gagné, 2005; Renzulli, 2005; Subotnik, Olszewski-Kubilius, & Worrell, 2011) achieves this goal of recognizing students’ high performances, and subsequently increasing their self-efficacy, while acknowledging the role effort plays in developing the skills needed for high performance.

Dweck’s research seems to indicate that gifted students may be more prone to a fixed theory of intelligence, which would be detrimental to their motivation. However, the modest amount of research examining the implicit beliefs of gifted children suggests a more complex interplay between these elements for high ability students. A recent study of academically gifted adolescents measured students’ implicit beliefs about giftedness and intelligence. Participants endorsed stronger entity beliefs for giftedness than intelligence (Makel et al., 2015), suggesting gifted students may view intelligence as more malleable than giftedness. Further, the gifted students in their study did not tend to endorse entity beliefs about intelligence. In a study of college freshman honors students, Siegle, Rubenstein, Pollard, and Romey (2010) found that high achieving students did not necessarily espouse an entity theory of ability.

In contrast to Dweck, Ziegler and Stoeger (2010) asserted that an entity theory of abilities does not necessarily lead to negative consequences for students with high abilities. Holding an entity view of intelligence would be maladaptive only for those with ability deficits, but would be beneficial for high ability students. Further, they hypothesize that incremental views/beliefs might actually be maladaptive for high ability students if/when individuals fear that it is possible that they could lose their existing abilities. However, viewing ability deficits as modifiable could be beneficial. Their preliminary research supports their hypothesis: Believing in fixed abilities may be beneficial to those with high abilities and detrimental to those with low abilities.

Talent Development and Self-Efficacy

Talent development models (Gagné, 2005, Renzulli, 2005, Subotnik et al., 2011) share at least one core tenet: Talents and abilities can be developed. Theories of talent development support the development of giftedness and recognize the that effort contributes to talent development. Therefore, what motivates gifted individuals to put forth effort is important.

We recognize both the importance of self-efficacy theory and mindsets in the development of talent. Students must believe they have the skills to perform a task before they will be motivated to attempt it. Therefore, being self-efficacious is an essential belief for high achievement and is included in the Achievement Orientation Model. However, to sustain focused effort over a long period of time to reach top levels of performance (Ericsson, Prietula, & Cokely, 2007), the efficacious belief must be tied to a growth mindset and an appreciation of the efforts to develop those talents. In other words, they must feel they control the talent development of their abilities through effort on their part. Having high self-efficacy and an approach goal-orientation, as well as showing a growth mindset, is more likely to positively affect the achievement process (Schunk & Pajares, 2013).

Goal Valuation/Meaningfulness

In addition to believing they have the skills to be successful, students must also value tasks and find them meaningful before they engage. This appears to be a critical issue for some gifted underachievers (McCoach & Siegle, 2003a). Many gifted underachieves have high self-efficacy, but fail to achieve in school because they do not value their schoolwork (McCoach & Siegle, 2003a). Individuals find tasks meaningful for different reasons. These reasons will vary from one person to another, but they often fall into four categories (Eccles & Wigfield, 1995). In academic settings, some students see themselves as good students. They identify as someone who performs well in school. This identity inspires them to work hard on whatever school-related task they encounter. Other students have a clear vision of their future and see the important role education plays in achieving future aspirations. They view school as a vehicle to future success. Some students do well in school when the topic interests them. Student interest is a powerful motivator for academic achievement. Interest is highly correlated with performance for gifted students across a variety of talent domains (Siegle et al., 2010). Finally, some students do well only when they see the immediate worth of the material they are learning. They may apply the material directly to their lives, or perhaps they may simply respond to being rewarded for doing well. Each of these examples represents a different impetus or motivation to achieve.

For many gifted students, the curriculum and instructional strategies they encounter in school are not meeting the intellectual stimulation and need for cognition they seek. Failure of the school environment to meet students’ needs can lead to declines in academic motivation and interest (Wang & Eccles, 2013). Therefore, valuing the goals of school and finding them meaningful are essential attitudes for achievement. Liddell and Davidson (2004) stressed the important role valuing tasks plays in achievement: “Students perform better on those skills that they value and this may be influenced by underlying motivation to master the skill” (p. 52).

Students whose interests and goals are incorporated into the curriculum show greater motivation and use self-regulatory strategies more often. They also have higher academic self-concept and subjective task values (Wang & Eccles, 2013). Effective curriculum for gifted students is appropriately challenging, is taught at an accelerated pace, has complexity in the organization of the content, and has greater depth (Little, 2012). Many gifted students already know much of the material they encounter in their regular classrooms (Reis, Westberg, Kulikowich, & Purcell, 1998). Gifted students generally enjoy learning and do not want to be bored in school. They often equate lack of challenge with boredom (Gallagher, Harradine, & Coleman, 1997). It is important that students encounter curriculum that is within their zone of proximal development (Vygotsky, 1978; Little, 2012). Curriculum models such as the Integrated Curriculum Model provide appropriate scaffolding for learners, thus being an influential motivator by differentiating curriculum, instruction, and assessment for learners within units of study (VanTassel-Baska & Wood, 2009).

Generally, gifted students naturally enjoy higher order thinking tasks (Rimm, Siegle, & Davis, 2018) and have a need for cognition (NFC). Need for cognition is “the tendency for an individual to engage in and enjoy thinking” (Cacioppo & Petty, 1982, p. 116). This overall stable motivational intrinsic trait is not necessarily domain-specific and is malleable (Cacioppo & Petty, 1986; Preckel et al., 2006). Students high in NFC are more likely to engage in learning processes, engage in complex thinking activities (Meier, Vogl, & Preckel, 2014), and earn higher school grades (Ackerman & Heggestad, 1997; Preckel et al., 2006). Preckel et al. (2006) found that lower values in NFC correlated with underachievement, even more strongly than achievement motivation. Students with NFC want to understand and find meaning in their experiences. Higher levels are associated with an increased appreciation of debate, evaluation of ideas, and problem solving (Dole & Sinatra, 1998).

Environmental Perceptions

Not only can students’ perceptions of self and their value of tasks lead to differences in academic achievement, students’ perceptions of the supportive nature of their environment can also lead to differences in achievement. Students must not only believe they have the skills to do well and value the related task, they must also believe their efforts are supported and will not be thwarted; therefore, putting forth effort is not a waste of time and energy.

Some environmental factors are within students’ control, others are not. The environmental perceptions construct in the AOM is similar to, but not synonymous with, Rotter’s (1966) locus of control. Students with external locus of control views believe others are in control and may question the support they receive in their environment. Therefore, external locus of control can negatively influence achievement with gifted students (Moore, 2006). However, students with internal locus of control beliefs may feel in control, but not necessarily supported by their environment. Therefore, achievement for students with internal locus of control can be thwarted when they perceive their environment blocking their efforts. Ogbu (1978) suggested that people put effort into areas where they believe they can be successful, and in environments where they believe they are supported.

Person-environment fit theory (French, Rodgers, & Cobb, 1974; Lewin, 1935) suggests that “outcomes result from an interaction between individuals and their environment” (Ritchotte et al., 2014, p. 185). Similarly, Ziegler’s Aciotope Model of Giftedness, supports the importance of interactions between the individual and the environment (Zeigler & Phillipson, 2012). The environmental perceptions factor captures the importance of the interaction between the person and the environment, as well as the perception of that environment on achievement motivation. Winton (2013) reported a positive relationship between teachers’ and peers’ support and intrinsic motivation. Gifted underachievers fixated on relationships with parents, teachers, and peers, and when students did not believe teachers or peers cared about them, it adversely affected their motivation. A variety of factors and interactions in the environment can influence students’ willingness to engage. Students’ positive perceptions of the school environment leads to higher levels of confidence for their academic self-concept (Brigandi, 2015). These perceptions of the environment are as important as the actual academic environment in promoting motivation and engagement in school (Wang & Eccles, 2013). While each of the components of self-efficacy, goal valuation, and environmental perceptions is essential, it is important to note that they interact and influence each other. For example, if students’ beliefs about school are positive, students are more likely to hold secure self-concepts (Wang & Eccles, 2013).

Siegle et al. (2014) found teachers influence all components of the AOM. In particular, teachers’ mastery of the content they taught was most influential with high-ability students. Knowledgeable teachers have clear mastery of the content they teach and appreciate the interdisciplinary relationship between content in different domains. These teachers build students’ self-efficacy to learn. Students are more likely to believe they can learn content when the teacher demonstrates mastery of it. They also trust that the classroom environment is one where they can learn. Knowledgeable teachers differentiate the content. They are not limited to prepared material. Knowledgeable teachers vary their instructional style. They encourage discussion. Teachers, with limited mastery of their content, are forced to strictly follow a prepared lecture format. Finally, knowledgeable teachers make interdisciplinary connections that promote meaningful learning experiences. When teachers are unfamiliar with their content, gifted students recognize their learning opportunities are limited and their self-efficacy to learn the content drops. Through differentiation and interdisciplinary connections, knowledgeable teachers help students see the meaning of the content they are encountering and value their classroom experiences.

Students who believe they can learn the material, find it meaningful, and trust their environment engage in the learning process, set realistic expectations, and self-regulate their learning. Although self-regulation may serve as the engine, propelling students toward achievement, the path to self-regulation and eventual achievement begins with positive views’ about one’s ability to succeed, the friendliness of the environment, and the importance of the task at hand.

Self-Regulation

Self-regulations’ importance for learning is well documented in the literature (Zimmerman, 2011). In some sense, the three attitudes we just described could be considered components of self-regulated learning. For example, goals are a central construct in most self-regulation theories (Locke & Latham, 2002; Pintrich, 2000; Zimmerman, 2000). Findings from meta-analyses support self-efficacy as an important contributor to self-regulation (Colquitt, LePine, & Noe, 2000). As Sitzmann and Ely (2011) noted, “self-regulated learning refers to the modulation of affective, cognitive, and behavioral processes throughout a learning experience to reach a desired level of achievement” (p. 421).

De Corte (2016) noted that self-regulation constitutes a major characteristic of adaptive and effective learning processes. He suggested

this means that, besides domain-specific content knowledge (in math, science, etc.), heuristic strategies, metacognitive knowledge, and positive emotions and beliefs towards learning, high-ability students need to acquire self-regulation skills. Thereby two aspects can be distinguished: skills relating to the self-regulation of one’s cognitive processes (metacognitive skills or cognitive self-regulation; e.g., planning and monitoring one’s problem solving processes), and skills for regulating one’s motivational and emotional processes (metavolitional skills or volitional self-regulation; e.g., keeping up one’s attention and motivation to solve a problem). (p. 1)

Baumeister, Schmeichel, and Vohs (2007) suggested that self-regulation has four components: standards of desirable behavior, motivation to meet standards, monitoring of situations and thoughts that precede breaking those standards, and willpower. Students need to be motivated to use self-regulations strategies; they need the will to engage in self-regulated learning as well as the skills to self-regulate (McCombs & Marzano, 1990). Certainly, self-regulation is essential for high levels of performance. In the Achievement Orientation Model, self-efficacy, goal valuation, and environmental perceptions provide prerequisite motivation; however, the ability to self-regulate at high levels is essential for obtaining eminence in a given domain (Ericsson, Krampe, & Tesch-Römer, 1993). Therefore, we cannot overstate the importance of self-regulation in achieving the highest levels of achievement.

Recent studies have explored self-efficacy and goal orientation beliefs and how they contribute to the learning process and self-regulation (Zimmerman, 2011; Zimmerman & Kitsantas, 2014). Self-regulation predicted sizable amounts of variance in students’ grade-point averages and performance on a standardized test (VSOL) in a study conducted by Zimmerman and Kitsantas (2014). Self-discipline, a close concept, did not predict a difference in GPA or performance on a standardized test; the concept of self-discipline focused more on overcoming performance problems than learning and motivation processes with self-regulation (Zimmerman & Kitsantas, 2014). In addition, students’ self-efficacy beliefs about their self-regulatory abilities are predictive of whether they use their self-regulatory systems, as well as their learning and performance outcomes (Zimmerman & Kitsantas, 2013).

Conclusion

Ultimately, for students to achieve academic success, a variety of factors need to be enacted, or prevented from occurring. Student environmental perceptions and self-perceptions affect academic achievement. Curriculum needs to be chosen carefully to include the interests and goals that are of high value to the student; it also needs to be accelerated when needed, taught in-depth, and with greater complexity in organization (Little, 2012; Wang & Eccles, 2013). Students who have high self-efficacy are more likely to create approach goal orientations, showing a growth mindset that is more likely to affect positively their achievement process (Schunk & Pajares, 2013). All of these attitudes and beliefs about achievement influence whether students achieve, to what extent students achieve, and in which context they achieve. Self-regulation helps propel students toward action. However, without the prerequisite attitudes we have described, students find is difficult to engage and develop self-regulation behaviors. Future studies need to evaluate the co-existing factors associated with the attitudes and beliefs that we have been described and how they interact and depend on each other. Ultimately, this research has the potential to clarify further factors related to gifted and talented students’ motivation to achieve and their willingness to self-regulate and strive for excellence.

References

Ackerman, P. L., & Heggestad, E. D. (1997). Intelligence, personality, and interests: Evidence for overlapping traits. Psychological Bulletin, 121, 219-245.

Ames, C., & Archer, J. (1988). Achievement goals in the classroom: Students’ learning strategies and motivation processes. Journal of Educational Psychology, 80, 260-267.

Artino, A. R. (2012). Academic self-efficacy: From educational theory to instructional practice. Perspectives on Medical Education, 1, 76–85. doi:10.1007/s40037-012-0012-5.

Bandura, A. (1977). Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychological Review, 84, 191-215.

Bandura, A. (1986). Social foundations of thought and action: A social cognition theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Baumeister, R. F., Schmeichel, B. J., & Vohs, K. D. (2007). Self-regulation and the executive function: The self as controlling agent. In A. W. Kruglanski, W. Arie, & E. T. Higgins (Eds.), Social psychology: Handbook of basic principles (2nd ed., pp. 516-539). New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Brigandi, C. B. (2015). Gifted secondary school students and enrichment: The perceived effect on achievement orientation. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, University of Connecticut, Storrs.

Brigandi, C., Siegle, D., Weiner, J., Gubbins, E. J., & Little, C. (2016). Gifted secondary school students: The perceived relationship between enrichment and goal valuation. Journal for the Education of the Gifted. doi:10.1177/0162353216671837

Cacioppo, J. T., & Petty, R. E. (1982). The need for cognition. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 42, 116-131.

Cacioppo, J., & Petty, R. (1986). Central and peripheral routes to persuasion: An individual difference perspective. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51, 1032-1043.

Colquitt, J. A., LePine, J. A., & Noe, R. A. (2000). Toward an integrative theory of training motivation: A meta-analytic path analysis of 20 years of research. Journal of Applied Psychology, 85, 678–707. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.85.5.678

Davies, J. L. (2012). Giftedness and underachievement: A comparison of student groups. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, University of Minnesota, St. Paul.

De Corte, E. (2016, April). Self-regulated learning: A major vehicle for talent development. Abstract for presentation at the Inaugural European-North American Summit on Talent Development, Washington, DC.

Dole, J. A., & Sinatra, G. M. (1998). Reconceptualizing change in the cognitive construction of knowledge. Educational Psychologist, 33, 109–128. doi:10.1080/00461520.1998.9653294

Dweck, C. S. (2006). Mindset: The new psychology of success. New York, NY: Random House.

Dweck, C. S. (2012). Mindsets and malleable minds: Implications for giftedness and talent. In R. F. Subotnik, A. Robinson, C. M. Callahan, & E. J. Gubbins (Eds.), Malleable minds: Translating insights from psychology and neuroscience to gifted education (pp. 7-18). Storrs, CT: The National Research Center on the Gifted and Talented, University of Connecticut.

Eccles, J. S., & Wigfield, A. (1995). In the mind of the actor: The structure of adolescents’ achievement task values and expectancy-related beliefs. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 21, 215-225.

Ericsson, K. A., Krampe, R. Th., & Tesch-Römer, C. (1993). The role of deliberate practice in the acquisition of expert performance. Psychological Review, 100, 363-406.

Ericsson, K. A., Prietula, M. J., & Cokely, E. T. (2007). The making of an expert. Harvard Business Review. Retrieved from http://www.coachingmanagement.nl/The%20Making%20of%20an%20Expert.pdf

Figg, S. D., Rogers, K. B., McCormick, J., & Low, R. (2012). Differentiating low performance of the gifted learner: Achieving, underachieving, and selective consuming students. Journal of Advanced Academics, 23, 53-71. doi:10.1177/1932202X1143300000

French, J. R. P., Jr., Rodgers, W., & Cobb, S. (1974). Adjustment as person-environment fit. In G. V. Coelho, D. A. Hamburg, & J. E. Adams (Eds.), Coping and adaptation (pp. 316-333). New York, NY: Basic Books.

Gagné, F. (2005). From gifts to talents: The DMGT as a developmental model. In R. J. Sternberg & J. E. Davidson (Eds.), Conceptions of giftedness (2nd ed., pp. 98-119). New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Gallagher, J., Harradine, C. C., & Coleman, M. R. (1997). Challenge or boredom? Gifted students’ views on their schooling, Roeper Review, 19, 132-136.

Heller, K. A., & Ziegler, A. (1996). Gender differences in mathematics and the sciences: Can attributional retraining improve the performance of gifted females? Gifted Child Quarterly, 40, 200-210.

Heller, K. A., & Ziegler, A. (2001). Attributional retraining: A classroom-integrated model for nurturing talents in mathematics and the sciences. In N. Colangelo & S. Assouline (Eds.), Talent development IV (pp. 205-217). Scottsdale, AZ: Great Potential Press.

Kirk, C. M., Lewis, R. K., Scott, A., Wren, D., Nilsen, C., & Colvin, D. Q. (2012). Exploring the educational aspirations-expectations gap in eighth grade students: Implications for educational interventions and school reform. Educational Studies, 38, 507-519. doi:1080/03055698.2011.6431114

Lewin, K. (1935). A dynamic theory of personality: Selected papers. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill.

Liddell, M. J., & Davidson, S. K. (2004). Student attitudes and their academic performance: Is there any relationship? Medical Teacher, 26, 52-56.

Little, C. A. (2012). Curriculum as motivation for gifted students. Psychology in the Schools, 49, 695-705. doi:10.1002/pits.21621

Locke, E.A., & Latham, G.P. (2002). Building a practically useful theory of goal setting and task motivation: A 35-year odyssey. American Psychologist, 57, 705–717

Long, L. C., & Erwin, A. (September, 2016). The effect of two interventions on high ability underachievers in an independent secondary school. Presentation at the Australian Association for the Education of the Gifted and Talented Conference, Sydney, Australia.

Makel, M. C., Snyder, K. E., Thomas, C., Malone, P. S., & Putaliaz, M. (2015). Gifted students’ implicit beliefs about intelligence and giftedness. Gifted Child Quarterly, 59, 203-212. doi:10.1177/0016986215599057

McCoach, D. B. (2002). A validation study of the School Attitude Assessment Survey. Measurement and Evaluation in Counseling and Development, 35, 66-77.

McCoach, D. B., Gable, R. K., & Madura, J. P. (2013). Instrument development in the affective domain: School and corporate applications (3rd. ed.). New York, NY: Springer.

McCoach, D. B., & Siegle, D. (2001). A comparison of high achievers’ and low achievers’ attitudes, perceptions, and motivations. Academic Exchange Quarterly, 5(2) 71-76.

McCoach, D. B., & Siegle, D. (2003a). Factors that differentiate underachieving gifted students from high-achieving gifted students. Gifted Child Quarterly, 47, 144–154.

McCoach, D. B., & Siegle, D. (2003b). The structure and function of academic self-concept in gifted and general education samples. Roeper Review, 25, 61-65.

McCombs, B. L., & Marzano, R. J. (1990). Putting the self into self-regulated learning: The self as agent in integrating will and skill. Educational Psychologist, 25, 51–69.

McNabb, T. (2003). Motivational issues: Potential to performance. In N. Colangelo & G. A. Davis (Eds.), Handbook of gifted education (3rd ed., pp. 417-423). Boston, MA: Allyn & Bacon.

Meier, E., Vogl, K., & Preckel, F. (2014). Motivational characteristics of students in gifted classes: The pivotal role of need for cognition. Learning and Individual Differences, 33, 39-46.

Moore, M. M. (2006). Variations in test anxiety and locus of control orientation in achieving and underachieving gifted and nongifted middle school students. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, University of Connecticut.

Multon, K. D., Brown, S. D., & Lent, R. W. (1991). Relation of self-efficacy beliefs to academic outcomes: A meta-analytic investigation. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 38, 30–38.

Ogbu, J. U. (1978). Minority education and caste. New York, NY: Academic Press.

Perez, P. M., Costa, J. L. C., Corbi, R. G., & Iniesta, A. V. (2016). The SAAS-R: A new instrument to assess the school attitudes of students with high and low academic achievement in Spain. Measurement and Evaluation in Counseling and Development. doi:10.1177/0748175616639106

Pintrich, P. R. (2000). The role of goal orientation in self-regulated learning. In M. Boehaerts, P. R. Pintrich, & M. Zeidner (Eds.), Handbook of self-regulation (pp. 451-501). San Diego, CA: Academic Press.

Preckel, F., Holling, H., & Vock, M. (2006). Academic underachievement: Relationship with cognitive motivation, achievement motivation, and conscientiousness. Psychology in the Schools, 43, 401-411.

Reis, S. M., Westberg, K. L., Kulikowich, J. M., & Purcell, J. H. (1998). Curriculum compacting and achievement test scores: What does the research say? Gifted Child Quarterly, 42, 123-129.

Renzulli, J. S. (2005). The Three-Ring Conception of Giftedness: A developmental model for promoting creative productivity. In R. J. Sternberg & J. E. Davidson (Eds.), Conceptions of giftedness (2nd ed., pp. 246-279). New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Rimm, S. B., Siegle, D., & Davis, G. A. (2018). Education of the gifted and talented (7th ed.). Boston, MA: Pearson.

Ritchotte, J. A., Matthews, M. S., & Flowers, C. P. (2014). The validity of the Achievement-Orientation Model for gifted middle school students: An exploratory study. Gifted Child Quarterly, 58, 183-198. doi:10.1177/0016986214534890

Robbins, S. B., Lauver, K., Le, H., Davis, D., Langley, R., & Carlstrom, A. (2004). Do psychosocial and study skill factors predict college outcomes? A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 130, 261-288.

Rotter, J. (1966). Generalized expectancies for internal vs. external control of reinforcement. Psychological Monographs, 80, 1-28.

Rubenstein, L. D., Siegle, D., Reis, S. M., McCoach, D. B., & Burton, M. G. (2012). A complex quest: The development and research of underachievement interventions for gifted students. Psychology in the Schools, 49, 678-694. doi:10.1002/pits.21620

Schunk, D. H. (1981). Modeling and attributional effects on children’s achievement: A self-efficacy analysis. Journal of Educational Psychology, 73, 93–105.

Schunk, D. H., & Pajares, F. (2013). Competence perceptions and academic functioning. In A. J. Elliot & C. S. Dweck (Eds.). Handbook of Competence and Motivation (pp. 85-104). New York, NY: The Guilford Press.

Siegle, D. (2012). Recognizing both effort and talent: How do we keep from throwing the baby out with the bathwater? In R. F. Subotnik, A. Robinson, C. M. Callahan, & E. J. Gubbins (Eds.), Malleable minds: Translating insights from psychology and neuroscience to gifted education (pp. 233-243). Storrs, CT: The National Research Center on the Gifted and Talented, University of Connecticut.

Siegle, D. (2013). The underachieving gifted child: Recognizing, understanding, and reversing underachievement. Waco, TX: Prufrock Press.

Siegle, D., & Langley, S. D. (2016). Promoting optional mindsets among gifted children. In M. Neihart, S. Pfeiffer, & T. L. Cross (Eds.), The social and emotional development of gifted children: What do we know? (2nd ed., pp. 269-280). Waco, TX: Prufrock Press.

Siegle, D., & McCoach, D. B. (2005). Motivating gifted students. Waco, TX: Prufrock Press.

Siegle, D., McCoach, D. B., & Shea, K. (2014). Application of the Achievement Orientation Model to the job satisfaction of teachers of the gifted. Roeper Review, 36, 210-220. doi:10.1080/02783193.2014.945219

Siegle, D., & Reis, S. M. (1998). Gender differences in teacher and student perceptions of gifted students’ ability. Gifted Child Quarterly, 42, 39-48.

Siegle, D., Rubenstein, L. D., & Mitchell, M. S. (2014). Honors students’ perceptions of their high school experiences: The influence of teachers. Gifted Child Quarterly, 58, 35-50. doi:10.1177/0016986213513496

Siegle, D., Rubenstein, L. D., Pollard, E., & Romey, E. (2010). Exploring the relationship of college freshman honors students’ effort and ability attribution, interest, and implicit theory of intelligence with perceived ability. Gifted Child Quarterly, 54, 92-101.

Simonton, D. K. (2005). Genetics of giftedness: The implications of an emergenic-epigenetic model. In R. J. Sternberg & J. E. Davidson (Eds.), Conceptions of giftedness (3rd ed.; pp. 312-326). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Sitzmann, T., & Ely, K. (2011). A meta-analysis of self-regulated learning in work-related training and educatioanl attainmetn: What we knkow and where we need to go. Psychological Bulletin, 137, 421-442.

Snyder, K. E., Barger, M. M., Wormington, S. V., Schwartz-Bloom, R., & Linnenbrink-Garcia, L. (2013). Identification as gifted and implicit beliefs about intelligence: An examination of potential moderators. Journal of Advanced Academics, 24, 242-258.

Subotnik, R. F., Olszewski-Kubilius, P., & Worrell, F. C. (2011). Rethinking giftedness and gifted education: A proposed direction forward based on psychological science. Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 12, 3-54.

Suldo, S. M., Shaffer, E. J., & Shaunessy, E. (2008). An independent investigation of the validity of the School Attitude Assessment Survey-Revised. Journal of Psychoeducational Assessment, 26, 69-82. doi:10.1177/0734282907303089

VanTassel-Baska, J., & Little, C. A. (2017). Content-based curriculum for high-ability learners (3rd ed.). Waco, TX: Prufrock Press.

VanTassel-Baska, J., & Wood, S. M. (2009). The Integrated Curriculum Model. In J. S. Renzulli, E. J. Gubbins, K. S. McMillen, R. D. Eckert, & C. A. Little (Eds.), Systems & models for developing programs for the gifted & talented (2nd ed., pp. 655-691). Mansfield Center, CT: Creative Learning Press.

Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Mind in society: The development of higher psychological processes. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Wang, M. T., & Eccles, J. S. (2013). School context, achievement motivation, and academic engagement: A longitudinal study of school engagement using a multidimensional perspective. Learning and Instruction, 28, 12-23.

Weiner, B. (1986). An attributional theory of motivation and emotion. New York, NY: Springer-Verlag.

Winton, B. J. (2013). Reversing underachievement among gifted secondary students (Doctoral dissertation). Retrieved from https://mospace.umsystem.edu/xmlui/bitstream/handle/10355/37824/research.pdf?sequence=2

Wood, R. E., & Locke, E. A. (1987). The relationship of self-efficacy and grade goals to academic performance. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 47, 1013-1024.

Ziegler, A., & Phillipson, S. N. (2012). Towards a systemic theory of gifted education. High

Ability Studies, 23, 3-30. doi:10.1080/13598139.2012.679085

Ziegler, A., & Stoeger, H. (2010). Research on a modified framework of implicit personality

theories. Learning and Individual Differences, 20, 318-326. doi:10.1016/

j.lindif.2010.01.007

Zimmerman, B. J. (2000). Attaining self-regulation: A social cognitive perspective. In M. Boekaerts, P. R., Pintrich, & M. Zeidner (Eds.), Handbook of self-regulation (pp. 13-39). San Diego, CA: Academic Press.

Zimmerman, B. J. (2011). Motivational sources and outcomes of self-regulated learning and performance. In B. J. Zimmerman & D. H. Schunk (Eds.), Handbook of Self-Regulation of Learning and Performance (pp.49-64). New York, NY: Taylor Francis.

Zimmerman, B. J., & Kitsantas, A. (2013). The hidden dimension of personal competence. In A. J. Elliot & C. S. Dweck (Eds.). Handbook of Competence and Motivation (pp.509-526). New York, NY: The Guilford Press.

Zimmerman, B. J., & Kitsantas, A. (2014). Comparing students’ self-discipline and self-regulation measures and their prediction of academic achievement. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 39, 145-155.